It's the 64 thousand dollar question.

Colleagues who read the blog agree with the logic of the thought process either can't come to grips with the idea that interest rates will ever rise substantially or... as is more often the case... they want to know... WHEN!

When will interest rates climb... even if it only as high as the 20 year historic norm of 8.25%?

My answer, as always, centres around sovereign debt.

Which is why this news article is of particular note.

The London Telegraph was reporting on news last week that the yield on 10-year Treasuries – the benchmark price of global capital – surged 30 basis points in just two days last week to over 3.9pc, the highest level since the Lehman crisis.

These developments are, of course, the trigger that caused Alan Greenspan to make his "the canary in the coal mine" comment.

As the Telegraph notes after the dramatic sell-off moves in US Treasuries last week sovereign debt fears have racheted up amongst investors and many are braced for further sell-offs as fears grow that the surfeit of US government debt is starting to saturate bond markets.

David Rosenberg at Gluskin Sheff said Treasury yields have ratcheted up 90 basis points since December in a "destabilising fashion" ,for the wrong reasons.

Growth has not been strong enough to revive fears of inflation, commodity prices peaked in January, and US home sales have fallen for the last three months (pointing to a double-dip in the housing market).

Rosenberg said the yield spike recalls the move in the spring of 2007 just as the credit system started to unravel. "The question is how the equity market is going to handle this back-up in rates," he said.

It's still unclear whether China is selling US Treasuries after cutting its holdings for three months in a row, or what its motive may be.

And looming over everything is the worry that markets will not be able to absorb the glut of US debt as the Fed winds down its policy of bond purchases, starting with an exit from mortgage-backed securities.

It currently holds a quarter of the $5 trillion of the MBS market.

The rise in US bond yields has set off mayhem in the 10-year US swaps markets.

As we noted last week, spreads turned negative touching the lowest level in 20 years. The effect was to drive credit costs for high-grade companies such as Berkshire Hathaway below that of the US government... it it a just a technical aberration?

Many are now speculating that the conditions are ripe for the bond vigilantes to rebel against the US government's wasteful ways.

Consider what's happening in the market for US government debt.

America remains in deep trouble. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that the world's largest economy will contract 2.8% this year, which is probably an underestimation.

Unemployment is rising fast and new figures show almost 10%c of US mortgages are now in arrears – up from less than 8%c in March and the highest "delinquency count" since records began almost 40 years ago.

No fewer than one in eight American households are now late paying their mortgage or have already endured foreclosure.

Ordinarily, an economic slowdown of this magnitude would bolster bonds – especially the market for Western government debt, which investors traditionally view as a safe haven.

But, despite the vicious downturn, the price of long-term US government bonds has been falling since the start of 2009, pushing up yields.

The reason is that the vast scale of the American government's indebtedness, has made investors less willing to fund US state spending by buying conventional (un-indexed) Treasury bonds.

Last week these fears came to a head, with the markets demanding a 3.75%c yield on 10 year Treasury notes, a six-month high and up from just 3.19%c the previous week.

As a result, 30-year wholesale mortgage rates surged from below 4%c to 4.74%c – again, in a single week – piling the pressure on cash-strapped households, many of whom are living in fear of their jobs.

Since the summer of 2007, when the credit crunch began in earnest, the US Federal Reserve has slashed interest rates from 5.25% to 0.25%.

These cuts were designed to support the economy by taking the pressure off highly-indebted banks, firms and households. But, whatever base rates have been set by the US Federal Reserve, the market is now driving the borrowing costs that companies, individuals and governments actually pay much higher.

For a long time many in the blogosphere have warned that the bond-market vigilantes would ultimately rebel against the Western world's profligate borrowing and spending.

That rebellion is now stirring in the most important economy on earth.

What happened in the US last week – almost a 60 basis-point rise in the 10-year Treasury yield, including a spike of 20 points in less than an hour – marks a significant turning of the screw.

And if interest rates are driven higher still, as the market asserts its authority, Greenspan's 'canary in the mine' comment will loom large.

Why did US Treasury yields rise so sharply last week? One catalyst was extremely soft investor demand for a $26bn (£16bn) issuance of US government debt.

Another was the latest bout of what we must call "quantitative easing" – when central banks create money to buy sovereign debt back off the markets in a bid to recapitalise the banks. Last week, alarmingly, dealers tried to sell the Fed far more bonds than it was willing to buy.

This spooked many bond traders, causing them to re-examine just how much QE the Fed can ultimately afford.

The recent decision by ratings agency Standard and Poor's to warn the UK over a potential sovereign downgrade has also had implications state-side. Many think S&P could end up downgrading the US.

Slowly but surely, global investors are becoming ever more concerned that QE, and massive sovereign debt issuance, than they are about fears of inflation.

And as they do, this will cause enormous Western price pressures.

Core inflation remains stubbornly high and rising oil prices and the destructive impact of the credit crunch on the supply chain aren't helping either.

Despite official warnings of deflation, the swaps market shows investors are increasingly unconvinced. Suspicion abounds that government in the US and UK, in particular, are now stoking inflation in order to monetise their massive debts.

In the 70s, US Treasuries went through a similar period in which confidence in the United States was severely shaken.

Rates on ten year bonds went from under 4% to 14 7/8%.

Overnight money went above 21%.

Confidence is what makes currency value and that is sundering fast.

When?

Watch the evolving story of western sovereign debt. History is playing out before our very eyes.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

When

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Surprise!.... well, not really.

In a move that seemed to stun all the interest rate naysayers, Royal Bank of Canada boosted the rate on five-year fixed-rate mortgages by 60 basis points to 5.85 per cent Monday, a move matched by other major banks.

That’s the biggest one-day jump in posted rates since 1996.

This despite the fact US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke pledged to keep the federal funds rate exceptionally low for an extended period and the Bank of Canada's pledge to keep the BOC rate where it is until summer.

As I said yesterday, a great many people assume that this will mean mortgage rates in the United States (and by extension, Canada) will also remain exceptionally low for an extended period of time.

Surprise!

Double surprise was the 60 point raise in rates.

“The rates are tied to our funding costs, which change day to day,” said an RBC spokesperson. “Our long-term funding cost has gone up significantly since December.”

As we have outlined before, mortgage rates are set by the bond market. And 5-year bond yields (which drive fixed mortgage rates) are now sitting at 2.90%, a 17-month high.

Now Monday's moves don't immediately affect Canadians with variable-rate mortgages because those rates are based on the Bank of Canada's prime rate (which has not changed - yet).

But the key point is that Monday's moves are a reminder that mortgage rates can rise before the Bank of Canada ever announces a change.

CIBC chief economist Avery Shenfeld said mortgage rates hikes are a trend consumers should expect to continue and had this bit of advice for consumers:

"Consumers are forewarned that when they look at borrowing today they have to factor in potentially higher costs. Consumers have to be aware in taking on debt at historically low interest rates that down the road they will be higher and have to leave room for their ability to pay those higher rates."

Yesteday's little tremor is but a blip in the larger scheme of things. Ultimately the real story will be impact of sovereign debt on the bond market.

Interest rates will be rising for the next few years. The mystery in the story will be in how fast they rise and how high they rise.

Since last winter we’ve had emergency interest rates as economic policy to encourage consumer spending.

And it worked.

Mortgage debt is now at a record levels, household debt exceeds that in the US and incomes have flatlined.

If the sovereign debt story plays out in the worst case scenario, no five year or ten year fixed term mortgage is going to save Canadians from what will result.

How many more surprises lie on the horizon?

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Monday, March 29, 2010

He said / he said

A buddy of mine likes to call me 'Chicken Little' with all my talk about the threat of rising interests rates.

And with his latest email taunt he sends along this news item from last Thursday in which US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke restated his observation that low inflation and a sluggish economy are “likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period".

Then my friend points an accusatory finger at last Monday's post in which I used the image of a dead canary in a coal mine to illustrate the looming threat of interest rates. This, he says, is my most recent example of 'irrational fearmongering'.

Irrational fearmongering?

Hmmm... we'll come back to that thought in a moment.

For now let's focus on what Bernanke said.

The Federal Reserve Chairman reiterated his position that "the federal funds rate" is likely to remain exceptionally low for an extended period.

A great many people assume that this will mean mortgage rates in the United States (and by extension, Canada) will also remain exceptionally low for an extended period of time.

Not true.

In the United States, the federal funds rate is the interest rate at which private depository institutions (mostly banks) lend balances (federal funds) at the Federal Reserve to other depository institutions, usually overnight. It is the interest rate banks charge each other for loans.

This has a direct impact on what your rate for borrowing will be, but it's important to note that it is not the determining factor on what interest rates will be for mortgages.

Mortgage rates are determined by Mortgage Bonds or Mortgage Backed Securities. As these items trade, the yields produced cause mortgage rates to fluctuate. In fact, it is not unusual to see them move in completely different directions than the Federal Funds rate.

[Note: the US Federal Reserve has been involved in an unprecedented program over the last year where they have been buying up Mortgage Backed Securities. Their willingness to purchase this debt - at low yields - is what has been keeping long term mortgage rates exceptionally low. The US Federal Reserve now 'owns' 10% of all US mortgages and there is tremendous concern what will happen when the program ends and they cease artificially supressing the mortgage rate)]

When the Fed lowers the short-term Federal Funds discount rate, this is designed to stimulate consumer spending on short-term credit, which affects credit card rates, some car loans and lines of credit. The short-term discount rate has little affect on long-term mortgage rates.

When the Fed cuts the rates, especially by a large or repeated percentage-point drop, people automatically assume that mortgage rates will fall. But if you follow mortgage rates, you will see that most of the time the rates fall very slowly, if at all. Historically, when the Feds have dramatically cut rates, interest rates remain almost identical to the rates established months before the cut as they do months after the cut.

Often what happens in the market is that investors spot a short-term stimulus (usually government stimulus) and they bail out of the safe haven of bonds (or mortgage backed securities) and move those dollars into stocks.

When this happens, we see a rally in the stock market and a sell-off of mortgage backed securities, both of which cause interest rates to go up.

It's the yields on these bonds that are important. When they cannot be sold, the yield has to go up to attract investors. And when the yield goes up - so does the mortgage rate.

That's why, on the day after Bernanke's comments, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan is making news and raining on his buddy Bernanke.

Greenspan claims the recent rise in Treasury yields represents a “canary in the mine” that may signal further gains in interest rates.

Canary in the mine?. Mr Greenspan, do tell.

Bloomberg reported the story and quoted a TV interview they conducted with Greenspan.

"Higher yields reflect investor concerns over this huge overhang of federal debt which we have never seen before. I’m very much concerned about the fiscal situation,” said Greenspan. These comments were made while discussing the trend towards an increase in long-term interest rates.

Last Monday I used the analogy that the rise in Treasury yields represented the stereotypical 'canary in the coal mine' alarm for interest rates. And by the end of the week, Alan Greenspan was saying exactly the same thing.

Neither of us considered Bernanke's comments about the Federal Funds Rate relative.

Nor should you.

Perhaps we should term it... 'rational' fearmongering.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Sunday, March 28, 2010

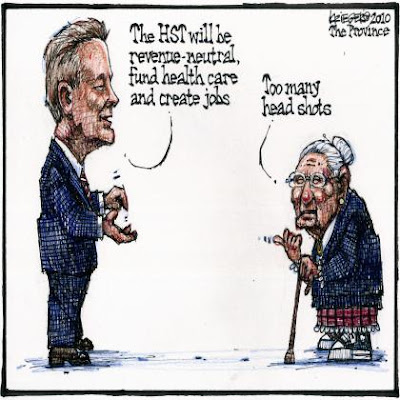

Sunday Funnies - March 28, 2010

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

Regular people... just gettin screwed

Over the next few years keep the polaroid camera handy.

Because there are sure to be many classic photo opportunities from friends in a situation like this one from Dany Cote of Calgary.

Our buddy Dan put down $20,000 on a Calgary condo in 2007 when he signed a presale contract to buy for $420,000.

Cote was pre-approved for the money and Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) agreed to insure the loan - so no worries, right?

Now we all know that the real estate market took a bit of a dive in 2008 and while it has completely re-inflated itself in Vancouver... apparently that's not the case in Calgary.

According to a recent appraisal, Cote's condo is only worth $335,000 now - down from the presale purchase price of $420,000.

And with that appraisal, CMHC will only insure a loan of up to $313,000.

What about CMHC's pre-approval, you ask?

Richard Cho, a spokesperson for CHMC, breaks the bad news.

"Typically, when a property is approved for CMHC insurance, CMHC does tend to honour that agreement during that period. However, there are times when an application is reassessed."

Ummm... reassessed?

Well, Dany-boy fell into the reassessment category and is seems that he's on the hook for the difference when the market went cold.

For our buddy Dany, that means he must come up with an $84,000 donation to complete the sale.

Does he have that kinda cash sitting around?

"My wife and I aren't in the position to advance the money and get over the bad situation. We're just regular people trying to get by." says Cote.

On Tuesday, the builder sued Cote for breach of contract seeking both the $20,000 deposit and the difference between the presale contract price and the condo's current market value.

Watch for this type of story to play itself over and over again once interest rates shoot up and trigger a drop in real estate values.

More and more Regular people just trying to get by are gonna be regular people just gettin screwed.

Isn't funny you don't see that scenario in the sales brochures?

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Who has seen the swirling winds of change?

But the breezy days of March (and a series of hawkish economic reports) appear to have changed expectations.

The Governor of the Bank of Canada spoke one word this week and market's stirred.

Carney went out of his way to remind Canadians that the promise of low rates is “expressly conditional” on low inflation. And inflation has been stronger than expected.

But it was the addition of that one adverb in a 3,131-word speech (prior to this low rates were merely 'conditional' on low inflation) that had the power to jolt financial markets.

And jolt they did.

Banker’s acceptance yields (which drives variable mortgage rates) hit a new 10-month high. 1-year bond rates are at a 13-month high. And Bloomberg says Canada’s 6-month overnight index swap rate, a gauge of what the overnight rate will average over that period, is at a one-year high.

Also up is the 5-year bond yield, which influences fixed mortgage rates. It made a new 5-month high this week.

Note the comments of economists now:

- "It increasingly seems as though the Bank of Canada is very tempted toward a June hike." - Eric Lascelles, chief rates strategist at TD Securities.

- “I cannot imagine a lower inflation forecast being unveiled come April, but can easily see a higher and sooner forecast.” - Derek Holt, economist at Scotia Capital. Holt thinks Carney may raise rates in June—possibly even April.

- "We still look for a first move in July, but the odds of something happening earlier are increasing a bit." - Michael Gregory, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets.

Who could have seen that coming? It's almost enough to send a chill up your spine, isn't it?

For those faithful readers for whom the fear of rising rates causes distress, consider this new option from TD Bank: a 10-year fixed rate of 4.99%.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

The Great Reckoning (... what'd I do?)

The survey found that more than 1/3 of Canadians said they were either struggling or unable to keep up with their finances.

And you can bet your bottom dollar, dear blog reader, that a good portion of the other 2/3's (the ones that said they were not struggling to keep up with their finances) are probably in the blissfully ignorant camp.

Self-assessment scales need to be taken with a grain of salt. Most of us will report that we are good drivers. Not all of us are.

As I have said time and time before, the story of Canadian Real Estate is going to be the story of interest rates. And those rates are going to be going up. The only question is... how high are they going to go?

Over the past week I have tried show that the current economic 'recovery' is all based on massive amounts of government stimulus. That western governments were within hours of a complete meltdown of the world's financial system and - in a desperate attempt to prevent a nuclear meltdown - the braintrusts of our national finances responded with knee-jerk reactions to halt a complete financial collapse.

Now they are struggling with the repercussions of those moves.

Worse... key members of that braintrust now admit that they made key mistakes that lead us to this precipice in the first place.

This is important since the 'emergency measures' taken in September/October 2008 were based on the those very flawed strategies, strategies which were once again drawn upon and taken to the extreme in the heat of potential disaster.

In Canada our own 'braintrust' made several catasrophic moves that are going to wreak havoc on our country in the years ahead.

When the 2007 real estate crash swept across the United States, Canadians smugly looked down at their noses at our American cousins and exalted in the superiority of our Canadian banking system.

But as we would come to learn, our Canadian banks barely escaped their own meltdown in 2008.

All five Canadian banks are levered at an average of 31:1. According to a report by Sprott Asset Management this implies that, if the Canadian banks’ tangible assets were to drop by 3%, their tangible common equity would effectively be wiped out.

When the recession started to appear in Canada, and real estate values began dropping here; government moved quickly to intercede.

If asset prices could be protected, it was rationalized, our nation could weather the recession and minimize the fallout.

To achieve this 'asset protection', Canadian Banks received $65 billion in liquidity injections from the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program. This is the official way of saying the Canadian Government, through CMHC, purchased insured mortgages from Canadian banks to provide additional liquidity on the asset side of their balance sheets.

The Bank of Canada then our Canadian Banks with an additional $45 billion in temporary liquidity facilities and there was also assistance from the Canada Pension Plan through the purchase of $4 billion in mortgages prior to the IMPP program for a total government expenditure of $114 billion.

But real estate values in Canada were plunging nothwithstanding. Que the next phase of the 'asset protection' strategy.

The CMHC was ordered by the Federal Government to approve as many high risk borrowers as possible to prop up the housing market (with entry level buyers) and keep credit flowing.

- In 2008 some 42% of all high risk applications were approved, a 33% increase over 2007.

- Between the beginning of 2007 and 2009 Canadian Banks increased their total mortgage credit outstanding listed on their books by only 0.01% -- possibly the smallest amount of change in post WWII history.

And it worked. Canadians jumped on the cheap, easy money and continued with a debt orgy that started in 2001.

- The Canadian mortgage securitizaton market has grown from $100 billion in 2006 to $295 billion by mid-June 2009.

- CHMC plans to expand securitization of debt to $370 billion by the end of 2009 as per the conservative government request.

- CMHC indicates in its plan that it will insure $813 billion via a combination of mortgage insurance and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) by the end of 2009.

- According to CHMC figures from 2008 and 2007 it is clear that CMHC has drastically exceeded their planned figures. It is expected that $812 billion is more than likely to be a minimum target.

- At these rates of progression the Government of Canada will in effect be insuring well over $500 billion in securitized mortgages and lines of credit by the end of 2010. The Canadian Government will also have issued over $600 billion in outstanding mortgage insurance.

By preventing the collapse of our real estate market; our financial system did not follow the path of our American cousins.

But at what cost?

Last Thursday we outlined the gigantic hole that Canadian households have plunged themselves into.

Debt held by Canadians is at an all-time high. Especially mortgage debt.

The policy of emergency interest rates and the moves to 'support' the Canadian banks can only succeed it there is a dramatic increase in the economic fortunes of the world economy.

But as I have outlined before, in order for the world economy to properly restructure we must still undergo a tremendous amount of deleveraging.

This will be a drag on any economic rebound for years to come.

Meanwhile, when the central banks start tightening monetary policy to mop up excess liquidity and stave off inflationary expectations and when capital markets start pushing back against massive government deficit funding and corporate debt rollovers, interest rates will have nowhere to go but up.

And, with it, will go mortgage servicing costs.

This process will not fully play out for 15 - 20 years, which means we will see very high interest rates for most of that period.

Since 2001 Canadians have been like the kids in the movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off. We have skipped class and finacially partied, having a grand old time.

At the end of that classic movie, Cameron Fry is left to deal with the ultimate reckoning from the reckless adventures of our heroes.

And while the movie glosses over that reckoning for Fry, that won't be the case for the 1/3 of Canadians say they are either struggling or unable to keep up with their finances when interest rates are at the lowest point in our nation's history.

Will Canada become a nation of Cameron Fry's?

When interest rates shoot up, Canadians are going to be caught in a debt vice of historic proportions. If 1/3 of Canadians are either struggling or unable to keep up with their finances now, what's it going to be like when the posted 5 year bank rate sits at 15%?

I distinctly remember a family friend, in the early 1970s, declaring that "the government will never allow mortgage rates to go over 10% because it would inflict too much financial harm on the people!"

By the end of the decade that family friend (as well as my parents) had to renew their home mortgages at 19% and 22% respectively.

How many are rationalizing in a similar delusional way today?

How many will be wiped out trying to service debt at interest rates at half of those 1980s levels?

How many will be uttering that infamous line... "what'd I do?"

================== Email: village_whisperer@live.ca Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Ferris... the miles aren't coming off!

Last week I started to talk about how I believe the stage is being set for a Canadian real estate collapse of historic and massive proportions.

Since the collapse of the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s, western governments have manipulated economic conditions so that we moved quickly from the unwinding of one bubble and into another.

Within a year of the collapse of the Internet Bubble, we moved seamlessly into the Real Estate Bubble. And within a year of the collapse of the Real Estate Bubble we have moved into another bubble… and it’s as if nobody can see that there are any similarities.

The only reason it worked in 2000 (and it didn’t really work then), is because we were able to borrow the money from the rest of the world and spend it. And we were able to live in the delusion that we were getting richer even when we were getting poorer.

We believed this because we looked at our asset prices (real estate and stocks) and we saw the prices going up and we said “hey, were actually getting wealthier”.

But we weren’t getting richer because we were spending money at the same time instead of saving money. We would borrow on the asset value and spend it consuming. And as we spent money, the government counted that money as GDP.

And as long as our GDP was rising then we thought our economy was growing.

But the whole time our GDP was going up, we weren’t measuring how much our wealth was going up. We thought we were okay because some appraiser said that our house was worth more. Or the stock market was still going up.

The 2008 Financial Crisis was simply the inevitable collapse of this ponzi mindset.

But when that collapse happened, it was SO intense…. SO profound... that our political masters panicked.

What happened in September and October 2008 had previously been considered completely impossible and totally unthinkable. We have always been told that the lessons of 1929 and the Great Depression had resulted in changes to the financial system so that NEVER AGAIN could the financial system come close to totally collapsing.

Yet we were within two hours of a complete collapse of our banking system and of our economy... and governments responded with panic measures.

They responded the same way they did each time there was a ‘financial emergency’ over the past several decades... with stimulus money and bailouts. Only this time they did it on a scale that has never been seen in the history of the world.

- In the 1990s the US Federal Reserve had been too easy and loose with money. Interest rates were too low and we created too much money. And that facilitated massive investments in the stock market.

- This created the 1997-1999 NASDAQ bubble. When that market crashed the government responded with even lower interest rates and easier access to stimulus money.

- And the exact thing that had happened with the Internet Bubble... now starts occurring with real estate.

We had the internet bubble because the US Federal Reserve was too easy with money.

Easy money allowed people to invest in companies that were tremendously overvalued. None of the dot.com stocks were paying dividends because none of the companies had a realistic chance of making money. But it didn’t matter. The frenzy was pushing stock prices up so people grabbed all the money they could and kept investing in them.

Recognizing what was going on, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan sought to intervene. In 1996 he talked about irrational exuberance and they took him to the woodshed for saying something negative. But he still went ahead and raised interest rates to correct the imbalance.

And the bubble burst.

Of course, when the stock market crashed, a lot of the malinvestments were exposed. A lot of the people working at the dot.com’s were going to have to be unemployed. A lot of companies who were given a lot of capital who shouldn’t have been given capital, were going to lose it all. And a lot of investors who invested foolishly who were going to lose a lot of money.

We were destined for a long, painful recession. Those malinvestments were going to have to be worked off. Capital would have to be reallocated to where it could be productively used, and labour would have to be laid off and rehired as that capital found productive uses.

As painful as it might be, it would be a necessary recesiion; the free market's way of correcting the imbalances.

But government intervened in the free market.

Rather than permit the painful process to play out, government would ‘stimulate’ the economy... again.

As always, the stimulus money created a catastrophe. This time in real estate.

During the dot-com, if you questioned the wisdom of what was happening, the reply was always, ‘you don’t understand the stock market’. Now, when anyone questioned the wisdom of what was happening in real estate, the reply was, ‘you don’t understand the real estate market’.

People were told rents don’t matter to real estate in the same way they said dividends don’t matter to stocks. What evolved was a rationalization that said all real estate would appreciate, year after year, for no other reason than a belief that real estate appreciates.

Everyone bought into the idea that it was going to go up... year after year... just because.

And it made no sense. Were incomes going up each year? Would you be able to charge 10, 20, 30 percent higher rents each year? No? Then why is the value going to go up 10, 20, 30 percent?

And the answer was... ‘it just will’.

And for the last nine years it has, fueled by easy money which is being invested in something that does not make fiscal sense – other than the value of the ‘asset’ seems to be rising by 10 – 30% each year.

The real estate bubble, and the financial services industry it created, has grown stupendously out of proportion.

The 2008 Financial Crisis is a result of the stimulus that created the dot-com bubble, the stimulus that tried to prevent the correcting of the dot-com bubble and the real estate bubble it all created.

A long, painful recession is needed to correct the imbalances.

But by responding in the same egregious manner to the 2008 Financial crisis, another catastrophe is inevitable.

Not only have we failed to correct the imbalances, western governments have liquefyed the system beyond any rational explanation in response to fears the entire system could collapse.

In the United States, the U.S. money supply has been expanding at an absolutely unprecedented rate (more than doubling the monetary base since the collapse of Lehman Brothers).

Fears of inflation – even hyperinflation – have been propagated throughout the blogosphere.

So why are we not experiencing rampant inflation?

Why is the U.S. dollar not falling through the floor?

Well, the truth is that all of this new money has gotten into the U.S. financial system but it is not getting into the hands of U.S. businesses and consumers. In fact, even though the money supply is exploding, U.S. banks have dramatically decreased lending. This has brought us to a very bizarre financial situation.

What we have seen is the U.S. government shovel massive amounts of cash into the U.S. financial system and then watch as the big banks sit on that cash and refuse to lend it. The biggest banks in the U.S. reduced their collective small business lending balance by another 1 billion dollars in November 2009.

That drop was the seventh monthly decline in a row. In fact, in 2009 as a whole U.S. banks posted their sharpest decline in lending since 1942.

So all of this money that the U.S. government pumped into the financial system has been doing American businesses and consumers very little good. That is why we can have a vastly increased money supply and very little inflation.

So if the banks are not lending the money to the American people, what are they doing with it?

One of the things they are doing with it is buying U.S. government debt. While U.S. banks have cut business lending by approximately 350 billion dollars since early 2009, they have meanwhile been purchasing approximately 300 billion dollars worth of U.S. Treasury securities.

So instead of loaning money to American businesses and consumers who desperately need it, a ton of this new money is being used to pump up yet another bubble. This time the bubble is in U.S. Treasuries. Asia Times recently described how this trillion-dollar carry trade in U.S. government securities works...

- Remarkably, the most aggressive buyers of US government debt during the past several months have been global banks domiciled in London and the Cayman Islands. They borrow at 20 basis points (a fifth of a percentage point) and buy Treasury securities paying 1% to 3%, depending on maturity. This is the famous "carry trade", by which banks or hedge funds borrow short-term at a very low rate and lend medium- or long-term at a higher rate. This works as long as short-tem rates remain extremely low. The moment that borrowing costs begin to rise, the trillion-dollar carry trade in US government securities will collapse.

Anyone who has dealt with carry trades in the past knows that when carry trades unwind they can do so very, very quickly and the results can be nightmarish.

And this one will unwind too, causing the bubble it is supporting (US Treasuries) to collapse.

You’ve heard it said that doctors 'practice' medicine and lawyers 'practice' law?

They say this for a reason. These 'professionals' never really know their craft. They learn about past mistakes and try to utilize tried techniques to address problems. When something goes wrong, they learn from it and ‘tweak’ their responses.

It is no different for economists, even those entrusted with running the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve (recall Saturday’s post of a paper by Alan Greenspan admitting how the Federal Reserve had failed).

The ‘experts’ panicked when the crisis of 2008 hit.

And they responded with tried techniques (plus a few new tricks) to address the problem.

The truth is that the U.S. financial system is a house of cards that could fall at any time. A lot of economic pain is on the horizon - it is only a matter of when it comes and how bad it is going to get.

And when it does come, interest rates are going to shoot up like nothing we have seen in over 30 years.

Tomorrow, the reckoning that Canada faces.

To read the next part of our series, click here.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Debt Market Update: Market 'downgrades' US from Triple A

Two-year notes sold by the Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc. in February yield 3.5 basis points less than US Treasuries of similar maturity.

Meanwhile debt issued by Procter & Gamble Co., Johnson & Johnson and Lowe’s Cos. also traded at lower yields in recent weeks.

This, folks, is what one chief fixed-income strategist described as an “exceedingly rare” event in the history of the bond market.

It means that key corporate debt now trades for lower yields than U.S. bonds of similar maturity.

We're at one of those historic moments in the credit market, when U.S. government bond yields are clearly no longer considered one of the safest investments in town.

It is a defacto move by the debt market to downgrade the value of US debt in advance of the 'official' ratings provided by agencies such as Moody's and Standard and Poor's.

Whatever credit ratings firms may say, markets have now made it pretty clear that the U.S. is far from a risk-free debtor. It's as if markets are already moving yields ahead of a potential cut to the AAA-rating.

And regardless of whether the credit ratings firms actually cut America's rating, the reality is that the old risk-free rating is essentially gone; even it still officially remains... the markets have figured it out.

(Note: this post is the second one today, in addition to the one directly below)

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

The Elusive Canadian Housing Bubble

Since you have dropped by, I offer a paper by Alexandre Pestov titled, "The Elusive Canadian Housing Bubble"... if you haven't already seen it elsewhere.

Canadian Housing Bubble ==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Sunday Funnies - March 21, 2010

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Alan Greenspan: The Fed Failed

Let's take a momentary break from our series for this must-read treatsie from Alan Greenspan.

I will post some concluding thoughts on this past week's series on Monday.

Today, however, check out this newly released paper from the former US Federal Reserve Chairman. In it, Greenspan discusses the causes of the financial crisis and the Fed’s failures leading up to it.

Greenspan is famous for his libertarian leanings and hands-off approach to Wall Street, but he now appears (finally) to be having some second thoughts.

Once celebrated as the “maestro” of economic policy, Greenspan has seen his reputation dim after failing to avert the credit bubble that nearly brought down the financial system. Now, in a 48-page paper that is by both analytical and apologetic, he is calling for a degree of greater banking regulation in several areas.

The report, which he presented Friday to the Brookings Institution, acknowledges his shortcomings in regulation and admits that, "regrettably, we did little to address the problem."

The former Fed chairman also acknowledged that the central bank failed to grasp the magnitude of the housing bubble but argued, as he has before, that its policy of low interest rates was not to blame. He stood by his conviction that little could be done to identify a bubble before it burst, much less to pop it.

“We had been lulled into a sense of complacency by the only modestly negative economic aftermaths of the stock market crash of 1987 and the dot-com boom,” Mr. Greenspan writes. “Given history, we believed that any declines in home prices would be gradual. Destabilizing debt problems were not perceived to arise under those conditions.”

Click here to see full document

To read the next part of our series, click here.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Arghhhhhh........

This will be the fifth post in our series this week. On Monday I will post a summary and my conclusions/thoughts.

Post #1 can be read here. Post #2 here. Post #3 here. And Post #4 here.

China as Canada's economic saviour

It's stunning the number of people who believe that, regardless of the US sovereign debt position, Canada will be okay because our resource based economy will be in demand by the emerging economic behemoth of China.

It won't be.

China's foreign exchange reserves stood at the astonishing level of $2.4 trillion at the end of 2009. About $2 Trillion of that is in US Treasuries.

That's $2 Trillion dollars in IOU's from the United States. If the sovereign debt crisis leads the United States to default, just who do you think is out all of that money?

Notwithstanding this small fact, the current economic situation in China is not as rosy as you might think.

Yes, they have invested an astonishing amount of foreign reserves in American debt, but did you know that China's proposed annual budget for 2010 will produce a record deficit?

Now, granted, this deficit is just $154 billion, or 2.8% of China's gross domestic product. In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office projects the US budget deficit for fiscal 2010 at $1.3 trillion. That's equal to 9.2% of GDP.

But let's take a closer look at China's finances. The following data comes to us from Jim Jurbak's journal.

There's a good argument to be made that if you look at all the numbers, instead of just the ones the budget magicians want you to see, China has far more debt than meets the eye.

If you look only at the current position of China's national government, the country is in great shape. Not only is the current budget deficit at that tiny 2.8% of GDP, but the International Monetary Fund projects the country's accumulated gross debt at just 22% of 2010 GDP. US gross debt, by comparison, is projected at 94% of GDP in 2010. The lowest gross-debt-to-GDP figure for any of the Group of Seven developed economies is Canada's 79%.

But China has a history of taking debt off its books and burying it.

If we go back to the last time China cooked the national books big time, during the Asian currency crisis of 1997, we can get an idea of where its debt might be hidden now.

The currency crisis started in 1997 with the collapse of the Thai baht—and. Like dominoes, the currencies of Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines collapsed. In each case, the country had built up an export-led economy financed by foreign debt. When the hot money that had been flowing in reversed (and started flowing out), that sent currencies, stock markets, and economies into a nosedive.

China escaped the first stage of the crisis because the country's tightly controlled currency and stock markets, and its economy, had kept out hot money from overseas.

China had built its export-led economy on domestic bank loans instead. The majority of bank loans, then as now, went to state-owned companies — about 70% of the total.

Those loans were all that kept the doors open at many of China's biggest state-owned companies. It's estimated that about 75% of China's 100,000 largest state-owned companies lost money and needed bank loans to continue operating.

That became a problem when, in the aftermath of the currency crisis, China's exports fell. That sent revenue plunging at state-owned companies that were already losing money. Suddenly, China's banks were sitting on billions and billions of debts that anybody who'd taken Bookkeeping 1 in high school could tell were never going to be paid.

This was especially a problem for China's biggest banks, all of which had ambitions to raise more capital — and their international profile — by going public in Hong Kong and New York. But no bank could go public with this much bad debt on its books.

So what did China do? They buried the bad debt.

The Beijing government created special-purpose asset management companies for the four largest state-owned banks, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the Agricultural Bank of China, the Bank of China, and China Construction Bank.

These asset management companies — China Cinda, China Huarong, China Orient, and China Great Wall — would ultimately wind up buying $287 billion in bad loans from state-owned banks. The majority of those purchases were at book value.

So how did the asset management companies pay for the purchase of that $287 billion in bad loans? They certainly didn't pay cash. Instead, they issued bonds to the banks in exchange for the bad loans. The bonds, of course, were backed by the promise that the asset management companies would gradually sell off or collect on the bad loans in time to redeem the bonds. And in the meantime, they'd pay the banks interest on those bonds.

Neat, huh? In one sweat move, the state-owned banks got $287 billion in bad loans off their books and turned deadbeat loans that would never pay off into streams of income from these bonds. To read more on this neat bit of financial engineering, check out this research paper.

Of course, that still left the little issue of where the asset management companies were going to get the approximately $30 billion in annual interest they had promised to pay the state-owned banks. There was also the small matter of how they were going to pay off these bonds when they came due in ten years, especially since the cash recovery rate on these bad loans would run at just 20.3% in the first five years.

But who really cared? The Beijing government and the state-owned banks had kicked the problem ten years down the road. (A favorite tactic of politicians, Republicans, Democrats, and Communists alike, is to punt, so that today's problem becomes somebody else's problem in the future.) The bonds issued by the asset management companies didn't have an explicit government guarantee, but everybody assumed that at some future date the government would either pay up or punt again.

The ten-year punt of 1999 came to earth in 2009, and, lo and behold, there has been some more magic.

In some cases — China Huarong, for example — the asset management companies simply declared that they were done disposing of bad debts, that profits were soaring, and that they were seeking strategic partners in preparation for a public offering.

In others cases, the magic was more complex. In October 2009, for example, China Cinda said it had secured government approval for a restructuring plan that would create a company to dispose of the $30 billion in bad loans still on Cinda's books. The company said it would then look for strategic partners in preparation for a public offering.

Who in their right minds would be a strategic partner and investor in one of these asset management companies? Well, how about one of the original state-owned banks, China Construction Bank, that Cinda had bought the bad loans from in the first place. "The hardest thing," China Construction Bank chairman Guo Shuqing said in this October 17, 2009 interview, "is evaluation."

Really?

When the government runs the books, does all the accounting, and decides what assets to send where, I think evaluation would be very easy. Any wonder, then, that today's huge run-up in loans — and bad loans — by China's banks is making some critics nervous?

The bigger problem, though, isn't so much China's big banks, but the country's local governments.

By now, everyone knows that the country's banks went on a lending spree in 2009.

On top of official government stimulus spending of $585 billion, banks, encouraged by the government, doubled their lending in 2009 to $1.4 trillion from the previous year.

(Please remember when judging these figures that China's economy was an estimated $4.8 trillion in GDP in 2009, according to the CIA World Factbook. We banter around such large numbers that it's easy to have these figures gloss our eyes over. To appreciate the size and scope of China's debt consider that estimated US GDP was about three times larger, at $14.3 trillion. So China's 2009 bank lending of $1.4 trillion would be equal to lending of $4.2 trillion in the United States, and China's $585 billion government stimulus package would equal a $1.7 trillion US package, more than twice the $787 billion size of the US stimulus package of February 2009.)

China's banks hit the ground running even harder in 2010, lending out an additional $309 billion in January and February. If the banks had continued at that rate, they would have passed the official lending ceiling of $1.1 trillion by August.

So China's banking regulators, spooked by the increase in bank lending, tightened the reins. For 2010, they set a lending target 20% lower than 2009 lending levels.

They raised reserve requirements so banks would have less capital to lend. And they told banks to hit the capital markets to raise an estimated $90 billion through 2011.

It's not clear that those steps will be enough to balance the huge number of bad loans that China's banks made during the lending boom. But China's regulators have clearly learned a lot about how to address a bad loan problem in the banking system since the 1997 currency crisis.

But as the US Federal Reserve has so amply demonstrated over the past decade, regulators tend to gear up to fight the last war. That leaves them vulnerable to the next crisis precisely to the degree by which it differs from the last one.

China's new debt problem is the thousands of investment companies set up by local governments to borrow money from banks and then lend it to local companies.

By law, China's local governments can't borrow directly. But the incentives for local governments to set up investment companies were huge.

By making loans to local companies, local governments could produce thousands of jobs and drive up the value of local enterprises. And by funding commercial and residential construction, they could drive up the price of land. Those results were important to local officials who often profited personally, but they were also essential to the survival of local governments. By law, those units also aren't allowed to raise their own taxes for local expenditures. To meet local demands—and to fulfill the directives issued by Beijing—local governments are dependent on frequently inadequate revenue transfers from Beijing and what they can collect from such transactions as local real estate sales.

So how much did these investment companies borrow and then lend?

Local government investment companies had a total of $1.7 trillion in outstanding debt at the end of 2009, estimates Victor Shih, an economist at Northwestern University and the author of Factions and Finance in China. That's equal to about 35% of China's GDP in 2009.

In addition, banks have agreed to an additional $1.9 trillion in credit lines for local investment companies that the companies haven't yet drawn down, Shih says.

Together, the debt plus the credit lines come to $3.8 trillion. That's roughly equal to 75% of China's GDP.

None of this, Shih points out, is included in the IMF calculation of China's gross-debt-to-GDP figure of 22%. If it were, the number would be closer to 100%.

It means China's actual gross debt is almost the same as the United States.

Exactly how important is this number, tho?

It depends on how many of those loans at local investment companies will go bad.

Shih estimates that about 25% of current outstanding loans — totaling $439 billion — will go bad. (For comparison, remember that in the aftermath of the 1997 currency crisis, the newly established asset management companies swallowed $287 billion in bad loans.)

It also depends on how much of China's huge reserves and huge base of personal savings are available to offset the debt.

So far, I've been talking about gross debt. But China, like Japan, has a huge domestic pool of savings it can use to buy debt. Economists point out that Japan has carried what looks like a crippling gross-debt-to-GDP ratio for years — 188% in 2007, 197% in 2008, 219% (estimated) in 2009, and 227% (projected) in 2010 — without disaster, because the country funds its debt internally from savings.

China, the argument goes, could easily do the same, so what's the problem?

The problem for both China and Japan is that it's not clear exactly how much of their huge pools of domestic savings are actually available in the long run to buy debt.

Japan has a woefully underfunded retirement system, and it's by no means clear how the population of the world's most rapidly aging country is going to pay for retirement.

China has, for all intents and purposes, no public retirement system. As a result of its one-child policy, the country has also begun to age quickly, and by 2030, its population will be as old as that of the United States.

In the US, the national accounts may lie about the effect of the problem by putting Social Security and Medicare off-budget on the argument that, since these programs have their own dedicated revenue streams, they don't count as part of the national debt.

But that lie aside, because the benefits of these programs are defined, it is possible to put a dollar figure on the government's future liabilities in this area (with all the uncertainty that comes with forecasting inflation, of course).

China isn't hiding any future liability for pensions or retiree health care off the books. The government hasn't promised future payments. In an accounting sense, then, there is no future liability that ought to be on the nation's books.

But that doesn't mean China won't have to consume some portion of its accumulated savings to pay for its post-65 population in 2030.

The country, either through the government or through private citizens, will have to cover the costs of old age, however it defines that cost.

And any savings it will use to pay for those costs really aren't available now to pay current debts.

I think the Chinese leadership is profoundly aware of the need today to not waste money that the country will need tomorrow.

That's one reason Beijing has taken steps recently to rein in local investment companies. On March 8, the Ministry of Finance announced plans to nullify all guarantees by local governments for loans taken out by their investment company vehicles. And the national government plans to sell $29 billion in bonds for local governments this year, giving those governments an alternative to setting up local investment companies.

But the big job — the reform of China's tax system so that local governments don't have to rely on real estate and stock market bubbles for funding — didn't make it on the to-do list announced by the National People's Congress this week and last.

I think you will find that as the United States founders under it's debt load, so will China. Particularly if the United States opts to default on any or all foreign treasury obligations or if the United States opts to monetize the debt.

The world is placing China, today, on the same lofty pedestal in which Japan was placed in the early 1980s.

The outcome will be the same.

To read the next part, click here.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

The question isn't what are we going to do... the question is what aren't we going to do!

This will be the fourth post in our series this week.

Post #1 can be read here. Post #2 can be read here. And Post #3 can be read here.

The North American Economy on life support

Western economies are witnessing a massive decline in new business and consumer borrowing. Consumers and businesses are being pressured to pay down outstanding debts plus widespread defaults and foreclosures forcing lenders to write off massive amounts of debts.

Credit is being sucked out of the consumer and corporate economy at a torrid pace while, conversely, huge amounts of credit are being grabbed by federal and local governments to finance their giant deficits.

The current economic recovery is being bought and paid for by government through stimulus programs. The idea is that once the economy recovers, the private sector will take over and the recovery will flourish.

The catch-22 is that new business and consumers can't get that credit, so the recovery won't take hold in a meaningful way.

Which is why a sovereign debt crisis — and future difficulties by governments to continue borrowing — is such a threat. If the U.S. economy is just limping along even with massive government support, what kind of paralysis will hit if the U.S. government cuts back that support to curtail out-of-control deficits?

One thing that is almost a given is that - unless forced to - liquidity and quantative easing will continue to be thrown at the system in an attempt to jump start the economy.

The bottom line is that with the massive supply of government bonds on the way, prices will be driven down and long-term interest rates up. Short of a miracle, there is little hope to avoid this outcome. Furthermore, as the federal deficit continues to grow out of control, the Great Credit Crunch is going to get even worse.

If credit remains scarce, the odds increase greatly for a long, multi-year recovery. If so there will probably be a violent double-dip recession beginning later this year.

With this as a backdrop, let's look at the current Canadian situation.

Canada

In Canada, the federal government responded to the crisis much as the USA and the UK did. Quantitative Easing and virtually 0% interest rates.

Have they learned nothing from the past decade?

Our own Bank of Canada Governor has alluded to the looming danger. On October 27th, 2009 Carney said that "we are awash in moral hazard. If left unchecked, this will distort private behavior and inflate public costs."

Moral hazard is an old bit of insurance jargon that describes how people misbehave when they think they are covered against risk.

And we are ‘awash in moral hazard’.

When the Bank of Canada cut interest rates to virtually zero and purposefully dumped cheap money into real estate; reckless buying and lending exploded over and above the bubble that blew up from 2001-2008.

CHMC reports show 57% of all real estate purchases in 2009 coming from first-time buyers (double the number from 2008) and all of those first time buyers are putting down the minimum 5% - meaning they are all utilizing CMHC’s bank-saving insurance.

And because CMHC - a federal government agency - backs all these high-risk mortgages with taxpayer dollars, all the risk for making these loans is removed from the banks. It enables Banks to lend to people who don't have money and little prospect of paying their loans off. It enables Banks to give these high risk borrowers the lowest mortgages rates available despite the fact they have the highest default risk.

Why? Because no risk accrues to the banks because of the CMHC insurance.

Eombine these government guarantees with Canada's supposed reputation as a 'fiscally prudent' country, and you have money flowing from around the world to help securitize these mortgages making money readily available to more Canadians for even more borrowing.

And just how deeply in debt are Canadians?

Jonathan Tonge has updated his excellent set of statistics on this issue on his blog. (Note from Tonge: The following graphs show the actual changes to outstanding credit [blue line]. They also show two other lines. Both make changes to the 1999 balance only [or 2002 in the case of household credit]. The inflation line shows what the credit would look like had the 1999 balance grown at the rate of inflation. The purpose of the disposable income line is to show how much debt would exist if the debt-to-disposable income ratio was maintained at the 1999 level - which even then was a historically high figure.)

Credit Card Balances - 1999-2010

Credit card balances are now up 458% in 11 years.

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to foresee a huge problem for Canadians as they try to sustain this debt level when the credit ceases to expand or more likely, contracts.

If Canada was going to have a resurgent ecnonomy with real wealth gains, then this would drive the debt to disposable income rate down. Real higher incomes provide savings and the ability to pay down debt.

As outlined above, this is looking highly unlikely.

The fact of the matter is that the current Canadian incomes and the economy are heavily inflated by debt.

Residential Mortgages

In 1999, outstanding residential mortgage debt was $399 billion. Eleven years later, it has expanded by 242% to $965 billion.

In 1999, outstanding residential mortgage debt was $399 billion. Eleven years later, it has expanded by 242% to $965 billion.The $965 billion is the figure quoted most often by the media. But it's missing an important trend that has occurred over the past ten years. Canadians have been tapping into the their home equity to finance purchases and mortgages at extraordinarily low variable interest rate through Home Equity Lines of Credit...

Personal Lines of Credit

Home equity lines of credit have become a vertible piggy bank for Canadian consumers. They use them to finance everything from cars to furniture to home renovations, and of course, additional mortgages.

Between 1999-2010, lines of credit grew 820% to $205 billion.

The total credit binge

As a result of credit cards, lines of credit and residential mortgages, household credit has expanded from $669 billion in 2002 to $1.41 trillion in 2009. Despite a small reprieve for a couple months in early 2009, it has been growing by roughly ten billion per month. By the end of 2010, Canada's household debt-to-disposable income will be roughly 155% (currently 146%).

In Canada the stage is set for a collapse of massive proportions.

Flaherty and Harper insist that Canada is sitting the catbird seat and that the Canadian economy will recover even while our largest trading partner, the United States, founders.

Recall that these are the same Masters of the Universe who said the growing recession in the United States in early 2008 wouldn't impact Canada at all.

Meanwhile 1/3 of Canadians are struggling financially.

Ask yourself, what happens when interest rates double, and the cost of debt does as well? Other studies suggest that Canadians are wildly overly optimistic about their financial picture. Canadians feel that they'll retire comfortably but can't verbalize or explain how that will happen. What happens when they come face to face with the reality that they are retired and not prepared?

Everyone says the nation will ride the economic recovery of the Far East and China, and that everything will be alright because of our commodity and resource rich land.

Tomorrow we will take a closer look at that.

To read the next part, click here.

==================

Email: village_whisperer@live.ca

Click 'comments' below to contribute to this post.